SANTA CRUZ LONG-TOED SALAMANDER

( Ambystoma macrodactylum croceum )

BY: Armando Pulido

http://www.californiaherps.com/salamanders/images/amcroceum.jpg

Description and Ecology

The long-toed salamander is a member of the mole salamander family ( Ambystomatidae ) which is characterized by its mottled black, brown, and yellow pigmentation, and its long outer fourth toe on the hind limbs. The ventral also know as its stomach has a surface that is sooty black. In order for the salamander to facilitate swimming it has a tail that is flattened from side to side. Adults have an average length from snout-to-vent length of 1.7 to 2.8 inches. They weigh approximately .1 to .4 ounces. When they are young, larvae have broad heads, three pairs of bushy gills and broad caudal fins that extend well onto the back. This salamander has two distinct life phases, it is first larvae that hatch from eggs laid in the water. After they hatch, they swim using their enlarged tail fin and breathe with filamentous external gills. They then transform into four -legged salamanders. After they become salamanders, they become terrestrial and breath with lungs. This species is found mostly found under wood, logs, rocks, and bark and other objects near breeding sites. The average adult lives to be about 10 years of age. This salamander is a carnivore when it is an adult. They eat small invertebrates such as worms, mollusks, insects, and spiders. In order to protect itself from predators, adults use their sticky skin secretions to deter predators. They can also vocalize with squeaks and clicks which can scare off predators. In terms of there breeding, reproduction is aquatic, adults become sexually mature at 1-3 years. Over night the male salamander will migrate overland during the heavy rain from October through February. The breeding process occurs in January and February. The way it works is that males enter the ponds first and wait for the females for several days up to a month. After the breeding process occurs females lay from 90-400 eggs in clusters. This clusters contain 1-81 eggs in shallow water that attach them singly or in loose clusters to the undersides of logs and branches. Eggs then hatch in 2-5 weeks.

Geographic and Population Changes

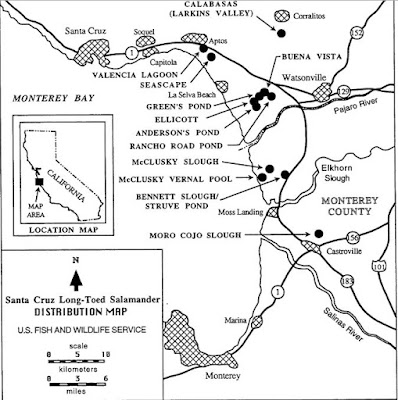

Since the Santa Cruz Long-toed Salamander is endemic to California, it has a a limited range of scattered populations in a reported 11 locations around the coast of Monterrey Bay in southern Santa Cruz counter and the northern edge of Monterey county. In December 2, 1954 at Valencia Lagoon, Rio del Mar, Santa Cruz county, this breeding pond was reduced in size by a highway construction along California State Highway. In 1969 this highway was converted into a freeway and it eliminated the Valencia Lagoon, which was a breeding pond for the salamanders. Around the same period of time another breeding pond was threatened by a proposed mobile home park which eventually made the salamander by listed as endangered.

Today only 23 populations of the salamander are known to exist. According to the recovery plan it is said that the Santa Cruz long-toed salamander has a distribution of three metapopulations, each with one or more subpopulations. These populations inhabit one or more ponds or sloughs and the surrounding upland habitats. Out of all the larvae, only 5 percent survive to metamorphosis. The other 95% of the population does not finish the race to metamorphose or is eaten by fish, birds or diving beetles.

In the figure below, this is the current distribution of the Santa Cruz long-toed salamander in Santa Cruz and Monterey.

http://www.californiaherps.com/salamanders/images/amcroceum.jpg

Listing Date and Type of Listing

As previously stated above, the construction of the California State Highway 1 caused destruction of the salamander habitat. Not only did this event harm the population of the salamander but the mobile home park also caused damages to another breeding pond. (Ellicott Slough) After these two events happened, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife service and the California Fish and Game Commission listed the Santa Cruz Long-Toed Salamander as an endangered species in March 1967. Other factors that contributed to this is the fact that this salamander has a limited distribution.

In the figure below, it shows the freeway which caused the salamander to be endangered.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/raymondyue/5583406075/player/f2645c9b97

Main Threats

Over the last 10,000 to 12,000 years climate and geologic activities have created the restricted and patchy distribution of habitats suitable for the Santa Cruz long-toed salamanders, resulting in a naturally restricted distribution of the subspecies. This disjointed distribution of the subpopulations have made the salamander susceptible to populations declines which are both human-associated and natural factors. Some factors include habitat loss and degradation, collection, predation by introduced and native organisms,infestation of parasites, geologic processes, and weather conditions. In Santa Cruz County and Monterey County, the main cause for this factors have been road construction and urbanization.

The figure below shows threats to the stability and persistence of Santa Cruz long-toed salamanders.

In 1954 is when the Santa Cruz long-toed salamander was discovered. Before the discovery of this salamander, Valencia Lagoon was being farmed when seasonally dry. Not only did this affect the lagoon but in less than a year after the discovery of the only know breeding pond, highway construction took place and the lagoon size was then reduced to half of its size. This really affected the salamander because it was unable to reproduce. As a result of destroying their habitat of an endangered species, Caltrans constructed an artificial pond. As a matter of fact multiple ponds were constructed to help the redevelopment of this species. This habitats created by humans allowed the salamander to survive.

Recovery Plan

Listed below are the steps essential to the recovery plan part 1:

1. Having self-sustaining populations of Santa Cruz long-toed salamanders at Valencia-Seascape, Larkins Valley, Ellicott-Buena Vista, and human-related mortality, and monitoring population;

2. Another step that can help is to find different breeding sites and suitable upland habitat areas.

3. The planning and implementing appropriate management strategies of the population status of Santa Cruz long-toed salamanders in the Merk Road drainage, in upper Moro Cojo Slough, and at any other new location found through the surveys.

4. Having the appropriate research to support the management of the Santa Cruz long-toed salamander habitats and populations.

5. Having the support of the public for this salamander through expanding public education and information.

The first objective is to recover the Santa Cruz long-toed salamander. The second part of the recovery plan is to recover the species to warrant delisting.

Listed below are the steps for the recovery plan part 2:

1. The first step is to have self-sustaining population, make sure that existing ponds remain, or become, functional breeding sites, improve the Valencia Lagoon, maintain the seascape pond at an appropriate level, come up with a comprehensive management plan for the Calabasas pond, continue adaptive management at Ellicott pond, working with the community to continue to have the breeding sites and upland habitats, putting out the effort to conserve Buena vista pond site, monitoring and managing Santa Cruz long-toed salamanders and their habitat at McClusky Slough, establish management actions at Moro Cojo Slough.

2. The management of upland habitats to provide adequate cover and food for nonbreeding salamanders, protect salamander habitat in Santa Cruz County, make sure that Salamander protection zone reguations are enforced, continue upland habitat restoration in sites, work with Willow Canyon Enterprise to come up with adequate Habitat conservation plan.

3. Build new ponds or restore existing ponds, analyze the possibility of establishing additional ponds in Larkins valley or other suitable places.

4. Reduce human-related mortality. prevent losses to the populations, create protection zones in Santa Cruz County, reduce the population of predators such as raccoons, opossums, and skunks.

5. Conduct surveys and identify habitat for protection.

6. Have the proper management for populations in the Merk Road and upper Moro Cojo.

7. Conduct research to habitat management such as to the determine the effects of methoprene, effects of mosauitofish/larval salamander interactions etc.

8. Have public education and information programs.

Personal Action:

There are many things one can do to help the preservation of the Santa Cruz long-toed salamander. Recycling is one easy way because it reduces your environmental impact. It eliminates waste that can be later dumped in environments where endangered species live such as the salamander. If you happen to live in the local areas to where these salamanders live, a good way to help them is by simply volunteering to pick up waste in their habitats. Another good way one can help with the preservation of the salamander is by buying land where these salamanders live and help preserve their habitat.

http://www.calhouncounty.org/recycle/wastetotals.html

Works cited

http://ecos.fws.gov/docs/recovery_plan/990702.pdf

"Find Endangered Species." Endangered Species. N.p., n.d. Web. 07 Dec. 2015. <http://www.fws.gov/endangered/>.

"Santa Cruz Long-toed Salamander - Ambystoma Macrodactylum Croceum." Santa Cruz Long-toed Salamander. N.p., n.d. Web. 07 Dec. 2015. <http://www.californiaherps.com/salamanders/pages/a.m.croceum.html>.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteit is interesting that you picked somewhat of a local species. since I am going into construction it is a good reminder to first focus on the ecology before the project. awesome blog!

ReplyDelete-Ryan O'Neill

#Bio227Fall2015

I did't realize that the highway could impact a species in such a big way. I will definitely think of this salamander next time I'm headed to Santa Cruz.

ReplyDelete#BIO227Fall2015

It's crazy that only 5% of larvae survive to metamorphosis. Cool read! I like that you mention volunteering as a personal action we can take.

ReplyDelete-Carla Pangan #BIO227Fall2015

The local aspect was nice. Makes you second guess yourself when you pass through the area. How tiny their remaining habitat is shocked me. I wish them all the best.

ReplyDelete-Mikki Okamoto